Guilt

This was my column yesterday.

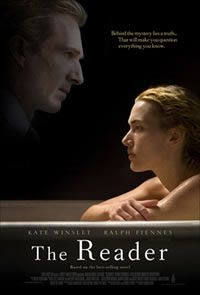

Too much attention, most of it fully deserved, is now being heaped on The Reader—both the film starring Kate Winslet, David Kross, and Ralph Fiennes, and the book written by Bernhard Schlink and translated into English by Carol Brown Janeway. Winslet won an acting award for the film at the recent Golden Globes Awards and is a shoo-in for the Oscars. The book was an international bestseller and was one of Oprah Winfrey’s picks for the year.

Too much attention, most of it fully deserved, is now being heaped on The Reader—both the film starring Kate Winslet, David Kross, and Ralph Fiennes, and the book written by Bernhard Schlink and translated into English by Carol Brown Janeway. Winslet won an acting award for the film at the recent Golden Globes Awards and is a shoo-in for the Oscars. The book was an international bestseller and was one of Oprah Winfrey’s picks for the year.

I read the book over the holidays and looked forward to the film mainly because I wanted to find out if another art form would be able to provide better treatment of such a complex material. I watched the film over the weekend and while I was awed with the astounding filmmaking, I came out of the experience more troubled—and with more questions. Of course it can be argued that this is probably the exact reaction that the film intended to create among its audience. If so, then the film succeeded.

The Reader is not a film that makes your heart soar after watching it. Instead, it opens up a lot of questions about collective guilt and responsibility. It makes us come to terms with the fact that events like the Holocaust are really difficult to explain and understand, and that despite the number of years that has elapsed, catharsis remains elusive.

What follows may be a spoiler for those who haven’t seen the film on DVD, so if you haven’t watched it and you intend to do so devoid of any preconceived bias, I suggest you stop reading now.

The Reader is first of all a love story— except that it’s a love story fraught with complications. He is 15 when it started; she was twice his age. Right off, the first stirrings of guilt are created as the audience is made to suspend judgment on the moral and psychological complications of the relationship and instead empathize with the situation the lovers find themselves in.

He reads to her the classics while she provides his sexual initiation—in erotic scenes that evoke memories of The Summer of ’42. The more observant viewers will note the “hints” that are subtly provided and which provides context to the complications that come later. She dislikes any form of text be it books, menus, or maps; she prefers being read to. This raises a number of questions. There’s also too much attention focused on her “uniform.”

which provides context to the complications that come later. She dislikes any form of text be it books, menus, or maps; she prefers being read to. This raises a number of questions. There’s also too much attention focused on her “uniform.”

In the book, there is a scene that gives readers a heightened sense of awareness about her situation. While traveling in the countryside, he leaves her in the morning in search of breakfast leaving a note behind to explain his absence. He returns to find her in a state of panic apparently because she thought he had left her. “But I left you a note,” he tried to explain. This scene is cut from the film.

She disappears from his life and when she reappears much later, the story takes a turn into a psychological-crime-suspense thriller. This time, he is a law student and she is on trial for one of the most atrocious crimes ever committed by mankind: Abetting murder as a Nazi guard at Auschwitz during the Holocaust.

The complications reach fever pitch at this point when she grapples with issues of pride and shame—not only about her role in the Holocaust, but also about her own literacy. He wrestles with his personal demons—on one hand, the desire for justice, his yearning for her, his duty to reveal what he knows, etc. Guilt, betrayal, shame, complicity are just some of the issues that make this part of the movie riveting.

The last part of the film brings the lovers to where they started—he reading to her the classics through cassette tapes that he sends to her in prison. There are two scenes that attempt to provide closure to the issues. First is his attempt to rekindle his relationship with his estranged daughter. And second, his anguished conversation with the main witness at her trial—the Auschwitz survivor whose book on The Holocaust sparked the trial to begin with.

The conversation between the two survivors deftly summarizes the moral dilemma presented by the plot. The Auschwitz survivor (played by Lena Olin with extreme coldness and palpable moral superiority) asks him what he is seeking: “Forgiveness for her or to feel better about yourself?”

The Reader is yet another take on the horrific events around the Holocaust, only this time, the central figure is one of the perpetrators of the crime. And this is what makes the premise complex, and at times, disturbing. The story allows us to make allowances for certain human frailties; we’re even allowed to empathize, perhaps even pity Winslet’s character.

I am sure there will be a lot of discussion and debate about the moral implications of the film. There will be those who will see the film as some kind of tacit endorsement of Nazi crimes.

The metaphors and issues presented —illiteracy, inter-generation relationship, complicity and soul-searching, the degrees of guilt and absolution—all make for a compelling experience, but do not really come together in the end; perhaps because they really are not meant to. Forgiveness and absolution are concepts we like to throw around but we know they are truly elusive when viewed against major tragic events such as the Holocaust.

Comments